Before customers exchange money for our product or service, they must see that exchange as one that benefits them. How do we understand their needs and goals to bring that about?

One way is to look at demographics, and then try to figure out what middle-class 37-year-old females on the East Coast have in common and what that does to our messaging etc. This is called studying personas. But this is abstract, and often doesn’t connect directly to a clear direction for our marketing.

Another approach is to look directly at the customer’s struggling moment—the moment when they realize “ouch, I couldn’t do that” and that they will need to hire a solution. This is what the Jobs to Be Done theory does.

Applying this theory, we can get much further into our customers’ needs and experiences and deliver not only products that will not only meet their needs, but a smooth sales experience that strongly connects their challenging situation to our solution.

Struggling moment

That struggling moment (again, when they realize “ouch, I couldn’t do that” and that they will need to hire a solution) is the seed of innovation. The customer has a painful need. Whoever or whatever best “understands the assignment” and provides the best solution will be hired to do the job.

The switch

Another foundational concept to understand in studying the customer is the switch. What is the customer going to stop doing when they start using our product? What’s the transformation they need to go through to get to that point?

What is a Job to Be Done?

Customers don’t just buy products. They “hire” them to do a job. Few people want to buy a quarter-inch drill—that purchase is a hire done by someone who wants a quarter-inch hole. So we can shift our focus from product language with its specifications, features, and benefits, to job language about outcomes and values.

Also, people aren’t just buying stuff, they’re buying what stuff does for them. Content is what you make for them, context is what you mean to them. Steak and pizza are two solutions you hire at different times. If you swap one for the other, you’ll have disappointing results.

- The context they’re in

- What they’re trying to do

- What were the hiring criteria of the current solution?

- What were the firing criteria of the previous solution (or of the current one if known)?

- What have they already hired?

The Jobs to Be Done interview

How do we understand their assessment of what a good deal is in reality vs. what they think and say it is?

We can interview people who’ve already bought.

Applying this to the Basecamp productivity application, they got 7 people who’d just bought Basecamp, and 7 people who were active users who had just switched to something else.

We sit down with the customer and get documentary-level detail of the whole timeline of the decision, going all the way back to the “first thought”, the first time they started to consider hiring something. That moment is important because it reveals the struggling moment that’s at the center of Jobs to Be Done.

Timeline framework

The timeline looks like this:

- First thought. “Maybe we should buy a new house.” After this the customer begins passively looking for a solution.

- Event 1. This can be a child getting sick or a job change, for example. After this the customer begins looking actively.

- Event 2. Something introduces an element of time limitation that prompts the customer to decide.

- The purchase. After this is the consumption of the solution.

- The accomplishment of the experience, after which is the satisfaction or other outcome feeling.

For a Jobs to Be Done interview, we don’t ask starting from the end, “tell me about it, did you like it?” We start from the beginning so that we have insights into their experience of the entire funnel from their first thought, since all of that informs our efforts. If we start from the end, people will report aspects of our product that they like that had no bearing on their hiring decision.

Forces of progress

| Business as usual | New behavior | |

| Promote a new choice | Push of the situation → | Pull of the new solution → |

| Block change | ← Habit of the present | ← Anxiety of the new solution |

Much marketing focuses on the “pull of the new solution” and neglects the other three. In-depth messaging about the customer’s problem motivates them out of “business as usual”, and careful attention to all the customer’s fears and uncertainties keeps them from feeling like they need to hit the brakes on a decision to stay safe.

Kano model of quality

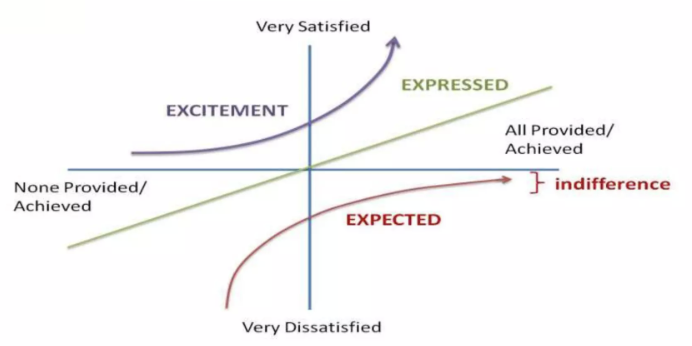

This graph is a little complicated, but I’ll explain it.

The vertical axis is level of satisfaction. The horizontal is the degree to which a certain promise has been delivered.

The three curved lines show the customer experience of three different categories of product promises: “exciting” features (think Pandora music access in a car), “performance” features (think gas mileage), and “expected” features (think brakes).

The brakes have to be there or there’s certainly gross dissatisfaction. But if they’re there, you only really get up to indifference. That’s the bottom line in red.

Gas mileage is just direct correlation—if it’s bad you’re fairly unhappy with the car, but not as bad as if the brakes don’t work. If it’s great you’re fairly happy with the car, but not outrageously delighted.

Souped-up features like Pandora online music integration don’t disappoint you much if they’re missing or don’t work, but can potentially really delight you if they work well.

From this model we can see that we don’t want to overinvest in the brakes. We should invest enough to get them into the “zone of indifference” and then work on the other two categories of things to get as much excitement into the customer experience as we can.

Image credits

- Drilling a hole in a plank of wood with a drill: image by freeimageslive.co.uk – gratuit | BY 3.0 Unported

Leave a Reply